There’s no escaping Santa this time of year. Whether you celebrate Christmas or not, he’s a mythical figure that is omnipresent. Just this week, I learned that Santa Claus, as we know him, is a product of NYC. Yes, you read that right kids, Santa wasn’t born on the North Pole.

Before he became the jolly, red-suited figure we recognize today, Europe was home to various gift-giving characters deeply rooted in religious traditions. Saint Nicholas, a 4th-century Christian bishop from Turkey, was renowned for his generosity to children and the poor. In the Netherlands, Sinterklaas evolved directly from his persona, arriving by boat in early December dressed in a bishop's robe. Germany's Christkind, a golden-haired angel, would deliver presents to well-behaved children. Italy's La Befana would fly on her broomstick during the Epiphany, leaving gifts for children.

As European immigrants arrived in the United States, these fractured religious traditions blended and secularized, creating a more universal figure that transcended religious denominations. Three key figures from New York played pivotal roles in cementing this transformation: Washington Irving, Clement Clarke Moore, and Thomas Nast.

Washington Irving, a religious skeptic and New York writer portrayed Christmas not as a rigid religious observance but as a unifying cultural moment. In his satirical work "A History of New York," published in 1809, he described St. Nicholas as a jolly, pipe-smoking character who flew over rooftops in a wagon, planting the seeds for the contemporary Santa Claus mythology. Just as Irving would later weave supernatural folklore into his legendary tale of Sleepy Hollow, he brought a similar imaginative touch to transforming St. Nicholas—showing his remarkable talent for reimagining traditional figures into more whimsical, folkloric characters. While Irving didn't wholly invent the character, he transformed the traditional religious figures into a more whimsical, folkloric figure.

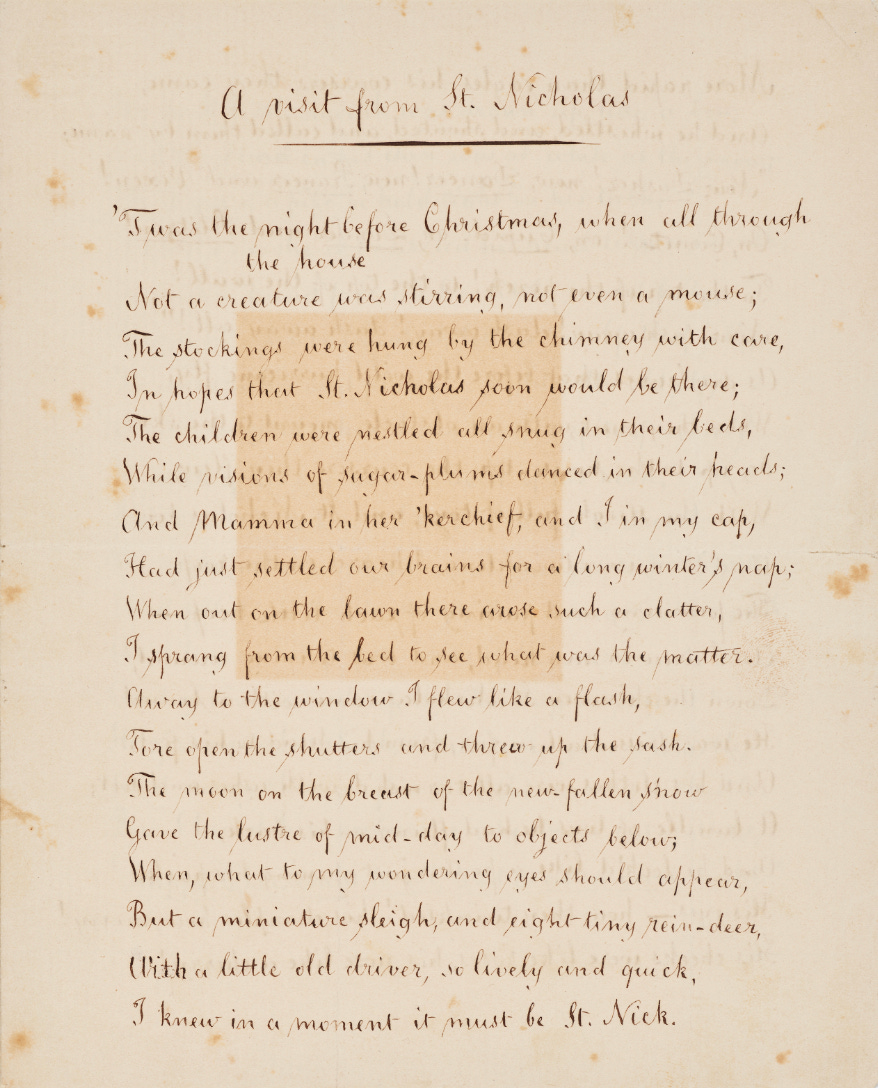

Inspired by Irving's depiction of an Episcopal clergyman, Clement Clarke Moore wrote the now-famous poem Twas The Night Before Christmas (originally called A Visit from St. Nicholas) in 1823 from his home in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan. Today's Santa Claus wouldn't be the same without his poem that transformed St. Nicholas into a more colloquial St. Nick—a jolly, magical figure who traveled in a sleigh pulled by reindeer and entered homes through chimneys.

The visual revolution of Santa Claus came through Thomas Nast, a German-born New Yorker whose illustrations in Harper's Weekly drew the modern Santa Claus into existence. During the Civil War, Nast used Santa as a symbol of national unity, dressing him first in a patriotic blue, then in the now-familiar fur-trimmed red suit. His images weren't just drawings—they were national propaganda that helped heal a fractured country.

These three men, each from different religious backgrounds, collectively contributed to creating a Santa Claus that was deliberately meant to be a more universal symbol of generosity and childhood joy, reflecting the melting pot culture of 19th-century America.

As the 19th century drew to a close, Santa Claus became more than just a mythical figure—he became a symbol of compassion and community support. In the early 1890s, the Salvation Army dispatched unemployed men dressed in Santa suits onto the streets of New York. These bell-ringing Santas weren't just collecting donations; they were embodying the spirit of generosity that the character represented. What began as a fundraising effort to provide free Christmas meals for needy families became a enduring tradition that continues today.

New York's commercial landscape completed the transformation. While other cities saw Christmas as a religious event, New York entrepreneurs saw it as an opportunity. Macy's created the first massive holiday marketing campaigns. F.W. Woolworth, operating from New York, imported European glass ornaments and made them affordable. FAO Schwarz turned toys from occasional gifts into must-have Christmas experiences.

The visual narrative of Santa Claus reached its commercial apex in the 1930s through Coca-Cola's groundbreaking advertising campaigns. Though illustrator Haddon Sundblom created these iconic images from Chicago, New York's Times Square became the ultimate stage for Santa's transformation into a commercial icon. Massive billboards featuring Sundblom's warm, grandfatherly Santa—with rosy cheeks, twinkling eyes, and a coca-cola in hand—dominated the bustling intersection. These larger-than-life advertisements did more than sell a beverage; they solidified a universal image of Santa Claus that would become instantly recognizable to millions of Americans, turning the character from a folkloric figure into a true national symbol.

As we see images of Santa this holiday season, it's worth remembering that this ubiquitous figure is far more than just a commercial mascot. He's a complex cultural creation and a testament to how writers and artists can transform the imagination of an entire nation—and, ultimately, the world.

Words of the Week

“What if Christmas, he thought, doesn’t come from a store. What if Christmas ... perhaps ... means a little bit more!” —Dr. Suess, How the Grinch Stole Christmas

Photo of the Week

If you pause for a moment and look up on Park Avenue at 32nd Street you’ll find this whimsical clock, originally known as The Silk Clock and now called The Wizard of Park Avenue. The clock was commissioned by the Schwarzenbach family, importers of silk, to adorn their headquarters. Designed by McKim, Mead & White (who also designed the Washington Square Arch) and artist William Zorach, and fabricated by Kunst Art Bronze Foundry. The clock features a silkworm and leaves motif is topped by a wizard with a wand and a blacksmith hammering a sword. Originally, a pair of moths flanked the clock, but they were removed during a renovation in 2014.

In 1926, The New York Times gave the following account of the clock’s installation:

"In behalf of the Schwarzenbach enterprises, a 'Silk Clock,' made of bronze, was dedicated yesterday morning ... before two hundred guests assembled in the street. A figure of Zoroaster, 'the mastermind and doer of all things,' is perched atop the clock. At his feet is a cocoon, and beyond sits a slave representing the 'primitive forces and instincts of man.' Every hour Zoroaster waves a wand, and the slave, rising at the will of his master, swings a hammer against the cocoon. Promptly the 'Queen of Silk' emerges from the cocoon, a tulip in her hand, and not until the hour has ceased striking does she disappear."

There are always new treasures to discover if you slow down for a moment to find them.

How delightful! And who knew Santa was/is a New Yorker...not me! Thanks for the history lesson - very interesting. Sending love and blessings to you and your readers, hoping the holiday spirit brings tidings of great joy to all.

Amazing Lia. I’m going to print this and give it to my grandsons. It’s such a great history of Mr Claus. 💕💕💕